Status Epilepticus

Dr. Elizabeth Lehto

Case

An 18-year-old female with a history of epilepsy presents via emergency medical services. She has been having generalized tonic-clonic activity for the past 5-minutes. Her sister who lives with her tells you she hasn’t taken her seizure medications for the past two weeks as she has been out of them. She has an abortive medication, but sister was unsure how to administer it, so no medication has been given.

What is status epilepticus?

Status epilepticus is either a single seizure lasting 5 minutes or longer, or multiple seizures without return to baseline lasting five minutes or longer.¹ Ideally, treatment for status epilepticus should begin within a 5-minute window.²

Focused Evaluation

During the initial resuscitation, a focused history and physical should be obtained.²

Key components of the history include:

Antiepileptics given prior to hospital arrival

History of epilepsy and other medical conditions (especially those that are associated with hypoglycemia, hyponatremia, or hypocalcemia)

Precipitating factors prior to the seizure (febrile illness, trauma, toxic exposure, change in antiepileptic medications)

Current medications

For patients with a history of epilepsy, history of treatment response

Allergies to medications

Key components of the physical examination

Airway, breathing, and circulation (ABCs)

Vital signs

Signs of head trauma

Signs of sepsis or meningitis

Seizure characteristics

Initial Management

While preparing to administer anticonvulsants, the ABCs need to be supported.

Airway/Breathing: Most patients can breathe adequately during a seizure as long as their airway remains patient.1 100% oxygen should be provided via nasal cannula or facemask. Suction devices should be available, including a large-bore suction device in case the patient vomits. Jaw thrust or airway adjuncts such as a nasal trumpet may be needed. Patients unable to protect their airway or with seizure lasting longer than 30 minutes should be intubated.²

Circulation/access: Intravenous (IV) should be established as soon as possible, if IV access isn’t able to be obtained within 5 minutes, an intraosseous line should be placed.

In general, status epilepticus does not independently cause hypotension. Bradycardia, hypotension, and poor perfusion are warning signs that point to hypoxia, and if present the patient should be intubated.²

Additionally, hypotension may develop in patients who require continuous infusion of medications for refractory status epilepticus and vasopressors may be needed.

Initial lab studies: Blood glucose, serum electrolytes, and calcium should be obtained on arrival. Additional lab work is dictated by the history and physical examination.

Treat Underlying Lab Abnormalities

Hypoglycemia: If bedside glucose is <70 mg/dL (3.89 mmol/L) an IV bolus of glucose should be given.

Infants and children up to 12 years:

5mL/kg of 10% dextrose solution

2 mL/kg of 25% dextrose solution

Children over 12 years:

1-2 mL/kg of 25% dextrose solution

Adults:

50 mL of 50% dextrose solution

100 mg of thiamine should be given before or concurrent with glucose to avoid development of Wernicke encephalopathy¹

Hyponatremia: Seizures are typically seen with serum sodium <120 mEq/L that develops acutely. Initial therapy consists of 3 to 5 mL/kg of 3% saline administered over 15 minutes. This can be repeated if sodium remains low and seizures are ongoing.

Hypocalcemia: Seizing patients with hypocalcemia should be treated with 5 to 7 mg/kg of elemental calcium (maximum single dose 540 mg of elemental calcium). This can be given as 0.6 mL of calcium gluconate 10 percent, which provides 5.6 mg/kg of elemental calcium. This should be administered over 5-10 minutes.²

First Therapy

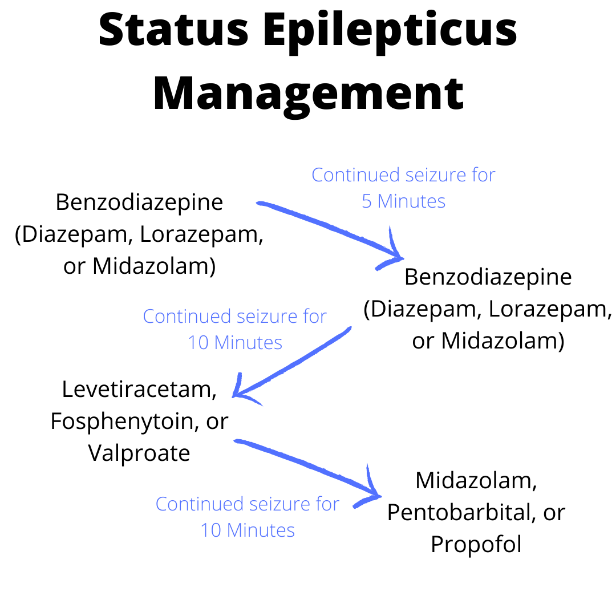

Benzodiazepines are the first line treatment for status epilepticus as they can rapidly control seizures.³,⁴ The three most commonly used medications are diazepam, lorazepam, and midazolam.

Diazepam: 0.5 mg/kg rectally (max of 20 mg) or 0.2 mg/kg IV or IO (max of 10 mg)

Lorazepam: 0.1 mg/kg IV or IO (max 4 mg)

Given slow push over 2 minutes and works to abort seizure in 2-5 minutes

Midazolam:

0.2 mg/kg for children <12 kg

5 mg for children weighting 13-40 kg

10 mg for patients weighing over 40 kg

Can be given intramuscular, intranasal, oral, buccal, or rectal, which makes it a great choice when IV access has not been obtained

Typically aborts a seizure in less than one minute

Often, the first dose of a benzodiazepine is given prior to arrival to the hospital. If patient continues to have seizure activity 5 minutes after an appropriate first dose of benzodiazepine has been given, a second dose should be given. Dosing of the second benzodiazepine is the same as the first.

Second Therapy

If the seizure continues for 10 minutes after two benzodiazepines, a second therapy with a long-acting antiepileptic is indicated.²,⁴ The most commonly used medications are levetiracetam, fosphenytoin, and valproate.

Levetiracetam: 60 mg/kg IV, max 4500 mg given over 5 minutes

No contraindications

Typically the choice of medication given in children

Fosphenytoin: 20 mg/kg IV, max 1500 mg given over 10 minute

Should be avoided in patients with Dravet syndrome (severe myoclonic epilepsy of infancy)

Valproate: 40 mg/kg IV, max 3000 mg over 10 minutes

Use with caution in women of childbearing age as it can cause birth defects

Can cause liver failure in patients with POLG mutation

Third Therapy

Patients who continue to have seizure 10 minutes after infusion of second therapy is given should be started on continuous infusion of midazolam, pentobarbital, or propofol.⁵ At this stage, patient will require endotracheal intubation, mechanical ventilation, continuous electroencephalogram (EEG) monitoring to know if seizure activity has resolved, and admission to the intensive care unit.

Midazolam: 0.2 mg/kg IV followed by continuous infusion of 0.05 to 2 mg/kg/hr

For breakthrough seizures an additional 0.1 to 0.2 mg/kg bolus can be give

Continuous infusion rate can be increased by 0.05 to 0.1 mg/kg/hr every 3-4 hours

Pentobarbital: 5 mg/kg IV followed by continuous infusion of 1 mg/kg/hr

Continuous infusion rate can be increased to 1 mg/kg/hr

Side effects include respiratory depression, hypotension, myocardial depression, and reduced cardiac output

Propofol: 1 to 2 mg/kg IV followed by continuous infusion at 1.2 mg/kg/hr

For breakthrough seizures can give additional 1 mg/kg bolus

Continuous infusion rates can be increased by 0.3 to 0.6 mg/kg/hr

Rarely used in children because dose and duration are associated with life-threatening propofol infusion syndrome (metabolic acidosis, rhabdomyolysis, and electrocardiogram changes)

Back to Our Case

Following arrival to the emergency department patient was placed on nasal cannula. Vital signs remained stable, and she was able to maintain her airway. IV access was obtained. She was given two doses of benzodiazepines and a dose of levetiracetam with cessation of seizure activity, and initial lab work was reassuring. . In discussion with patient, she had recently moved to the area for college and had not established care with neurology, so has been unable to get a refill on her medications. You are able to arrange follow up with a local neurologist and provide education on the importance of taking her medications.

Bottom Line

Status epilepticus is either a single seizure lasting 5 minutes or longer, or multiple seizures without return to baseline lasting five minutes or longer. Ideally, treatment for status epilepticus should begin within a 5-minute window. ABCs should be supported while preparing antiepileptic medications.

First line treatment is with benzodiazepines: diazepam, lorazepam, or midazolam. If the patient continues to have seizure activity 5 minutes after first benzodiazepine has been given, a second dose should be given.

If the seizure continues for 10 minutes after two benzodiazepines, a second therapy with a long-acting antiepileptic is indicated (levetiracetam, fosphenytoin, or valproate).

Patients who continue to have seizure 10 minutes after infusion of a second therapy should be started on continuous infusion of midazolam, pentobarbital, or propofol. At this stage, patient will require endotracheal intubation, mechanical ventilation, continuous electroencephalogram (EEG) monitoring to know if seizure activity has resolved, and admission to the intensive care unit.

Elizabeth Lehto, D.O.

University of Louisville | UL · Department of Pediatrics | Doctor of Pediatric Emergency Medicine

Dr. Elizabeth Lehto is a Pediatric Emergency Medicine Attending at Norton Womens and Children’s Hospital. Dr. Lehto attended Midwestern University Arizona College of Osteopathic Medicine and completed her residency and fellowship at the University of Louisville.

References:

Betjemann JP, Lowenstein DH. Status epilepticus in adults. Lancet Neurol. 2015;14(6):615-624.

Wilfong A. Management of convulsive status epilepticus in children. 2021; https://www.uptodate.com/contents/management-of-convulsive-status-epilepticus-in-children.

Drislane FW. Convulsive status epilepticus in adults: Treatment and prognosis. 2021; https://www.uptodate.com/contents/convulsive-status-epilepticus-in-adults-treatment-and-prognosis.

Crawshaw AA, Cock HR. Medical management of status epilepticus: Emergency room to intensive care unit. Seizure. 2020;75:145-152.

Vasquez A, Farias-Moeller R, Tatum W. Pediatric refractory and super-refractory status epilepticus. Seizure. 2019;68:62-71.