Pediatric Head Trauma: To CT or not to CT?

Dr. Elizabeth Lehto

Case

Sally is a 3-year-old female who presents after a head injury. She was at home jumping from the couch to the coffee table when she fell and struck the front of her head on the ground. The couch is about 1.5 feet off the ground. She cried initially but is now calm. She did not pass out and there was no vomiting. Her mom is very worried about the possibility of bleeding and is asking you if imaging is needed. What do you tell her?

Introduction

Intracranial injury is the leading cause of death and disability in children. Minor head injuries present the greatest diagnostic dilemma in the emergency department (ED), as minor blunt head trauma is a common occurrence in infants and children. While it is typically not associated with brain injury, a small number of children with minor blunt head trauma do have clinically important traumatic brain injury.

Computerized tomography (CT) imaging is highly sensitive for identifying injuries that require neurosurgical intervention. CT imaging is useful in that it allows for early and accurate identification of intracranial injuries, which can reduce morbidity and mortality. Additionally, it can decrease concerns about missed injuries. However, CTs are not without risk. There is a dose dependent association between radiation exposure and cancer risk. This risk is greater with younger age and for females.1 Cost of imaging is also worth considering, especially for accident prone children who may be seen in the ED multiple times for minor head injuries. Therefore, it is important to minimize overuse of CT in those children who are at low risk for brain injury.

What is Considered Minor Blunt Trauma?

Blunt head trauma is considered minor in patients who have a history of or physical signs of head trauma and:

Glasgow Coma Score (GCS) of 14-15

Normal neurological exam

No evidence of skull fracture on physical exam (no palpable skull defect and no signs of basilar skull fracture)

What is Considered a Clinically Important Traumatic Brain Injury?

A clinically important traumatic brain injury is defined as:

Presence of an intracranial injury (epidural hematoma, subdural hematoma, or cerebral contusion) seen on CT associated with one of the following

Neurosurgical intervention such as surgery or invasive intracranial pressure monitoring

Intubation for the management of head injury

Hospitalization directly related to the head injury for two nights or longer

Death

OR

Depressed skull fracture requiring operative elevation

OR

Clinical findings of basilar skull fracture [Periorbital ecchymosis, Battle sign, hemotympanum, cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) otorrhea or CSF rhinorrhea]

Traumatic brain injury that is not considered clinically significant is any intracranial injury on CT that does not require intervention or prolonged hospitalization.2

How Do I Decide Who to CT?

Clinical decision rules help determine who is low risk for clinically important traumatic brain injury.

The Pediatric Emergency Care Applied Research Network (PECARN) clinical decision rule is the largest study on minor pediatric head injury and has undergone external validation.2-4 PECARN has separate criteria for children under 2 and for children age 2 and above. Aspects of the history and physical examination divide patients in to high, intermediate, and low risk criteria.

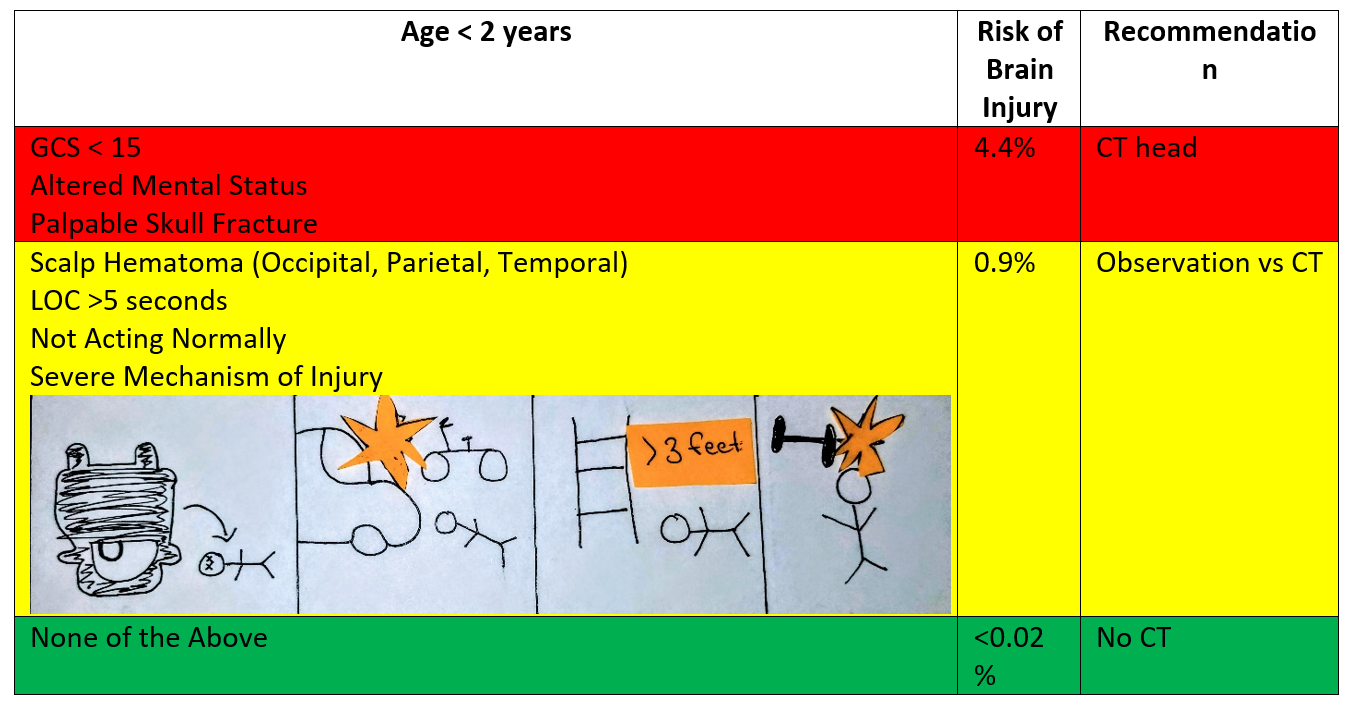

Patients <2 Years

High Risk

Patients with a GCS <15, altered mental status, or palpable skull fracture are determined to be high risk. These patients have a 4.4% risk of clinically important traumatic brain injury, and head CT is recommended.

Intermediate Risk

Patients with a hematoma on the occipital, partial or temporal scalp, loss of consciousness (LOC) for ≥ 5 seconds, severe mechanism of injury, or not acting normally per parent are at intermediate risk. Severe mechanism in this age group is a fall greater than 3 feet; motor vehicle accident (MA) with ejection, rollover, or fatality; bike or pedestrian struck by a vehicle while not wearing a helmet; or struck by a high impact object.

These patients have a 0.9% risk of clinically significant traumatic brain injury. These patients can be observed in the ED for 4 hours for signs of symptom progression or a CT can be obtained. Decisions about observation or CT are guided by physician experience, parental preference, multiple or isolated findings on examination, worsening signs or symptoms during observation period, and age (lower threshold for CT in patients <3 months).

Low Risk

Any patients who don’t have any of these findings are considered low risk, with a <0.02% risk of clinically important traumatic brain injury and CT head is not recommended.

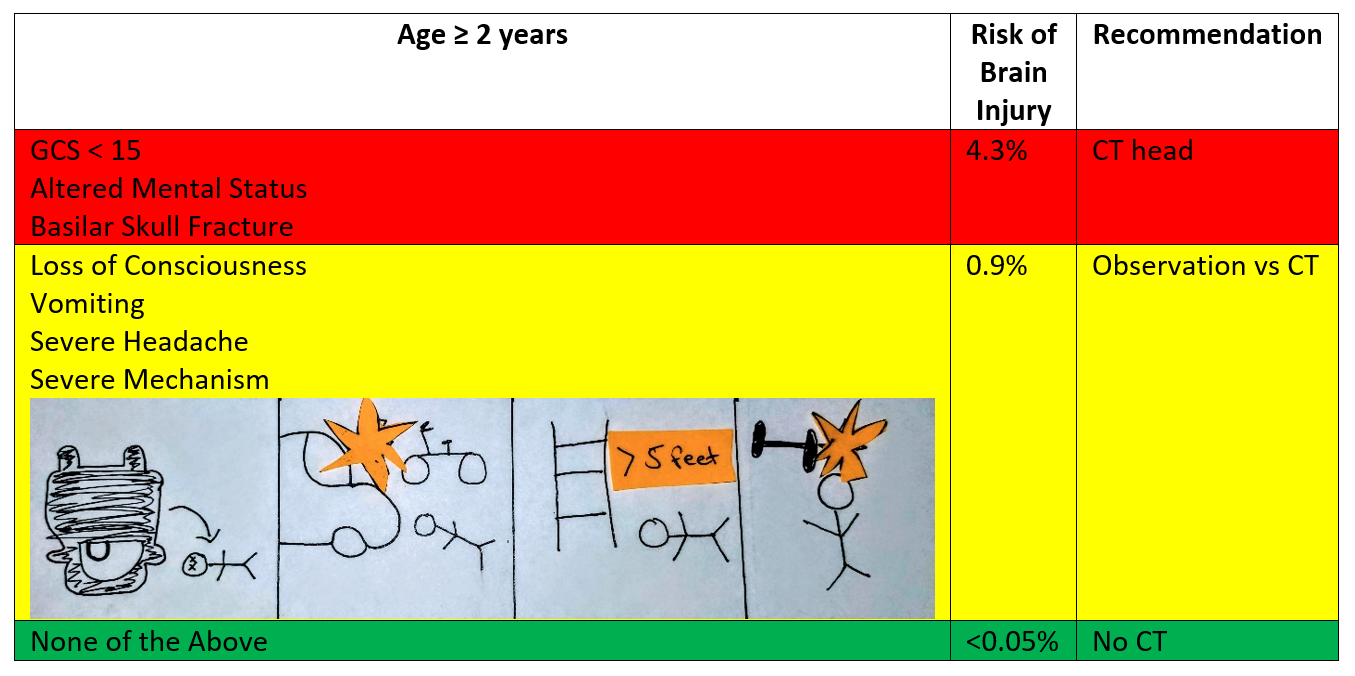

Patients ≥2 Years

High Risk

Patients with a GCS <15, altered mental status, or signs of basilar skull fracture are determined to be high risk. These patients have a 4.3% risk of clinically important traumatic brain injury, and head CT is recommended.

Intermediate Risk

Patients with loss of consciousness, vomiting, severe mechanism of injury, or severe headache are at intermediate risk. Severe mechanism in this age group is a fall greater than 5 feet; motor vehicle accident (MA) with ejection, rollover, or fatality; bike or pedestrian struck by a vehicle while not wearing a helmet; or struck by a high impact object.

These patients have a 0.9% risk of clinically significant traumatic brain injury. These patients can be observed in the ED for 4 hours for signs of symptom progression or a CT can be obtained. Decisions about observation or CT are guided by physician experience, parental preference, multiple or isolated findings on examination, worsening signs or symptoms during observation period.

Low Risk

Any patients who don’t have any of these findings are considered low risk, with a <0.05% risk of clinically important traumatic brain injury and CT head is not recommended.

Back to Our Patient

After reviewing the PECARN head trauma criteria, you determined that the patient was at low risk for clinically significant traumatic brain injury. After a discussion with mom about the risks and benefits of CT, decision was made not to CT. The patient was monitored briefly in the ED, during which time she remained at her baseline mental status and was able to drink apple juice without emesis. She was discharged home with strict return precautions including to return if there was any change in mental status, more than 4 episodes of vomiting, or mom becomes concerned that she is not acting like herself.

Elizabeth Lehto, D.O.

University of Louisville | UL · Department of Pediatrics | Doctor of Pediatric Emergency Medicine

Dr. Elizabeth Lehto is a Pediatric Emergency Medicine Attending at Norton Womens and Children’s Hospital. Dr. Lehto attended Midwestern University Arizona College of Osteopathic Medicine and completed her residency and fellowship at the University of Louisville.

References

Pearce MS, Salotti JA, Little MP, et al. Radiation exposure from CT scans in childhood and subsequent risk of leukaemia and brain tumours: a retrospective cohort study. Lancet. 2012;380(9840):499-505.

Kuppermann N, Holmes JF, Dayan PS, et al. Identification of children at very low risk of clinically-important brain injuries after head trauma: a prospective cohort study. Lancet. 2009;374(9696):1160-1170.

Ide K, Uematsu S, Hayano S, et al. Validation of the PECARN head trauma prediction rules in Japan: A multicenter prospective study. Am J Emerg Med. 2020;38(8):1599-1603.

Lorton F, Poullaouec C, Legallais E, et al. Validation of the PECARN clinical decision rule for children with minor head trauma: a French multicenter prospective study. Scand J Trauma Resusc Emerg Med. 2016;24:98.