Shots, Shots, Shots….or Not? Responding to Vaccine Hesitancy

Dr. Elizabeth Lehto

Immunizations have made a significant impact on the health of our patients by decreasing the rate of vaccine preventable illnesses. However, increasing numbers of people are expressing concerns about vaccine safety, vaccine side effects, and the necessity of vaccines in general. For some, like pediatricians, discussing the importance of vaccination and addressing vaccine hesitancy has become a well-versed part of patient education. With the COVID-19 pandemic, conversations about vaccines are now something that providers in every specialty should consider incorporating into their patient encounters.

Patterns in Arguments Against Vaccines

Vaccine hesitancy is influenced by a number of factors including issues with confidence (families do not trust the vaccine or provider), complacency (do not perceive a need for a vaccine or do not value the vaccine), and convenience (access to vaccines).¹ Vaccine hesitant patients are a heterogenous group that may accept all vaccines but remain concerned about them, refuse or delay some vaccines but accept others, or refuse all vaccines.¹

One of the perceptions among vaccine critics is that the vaccines cause more harm than the disease they were designed to prevent.² Often times this is actually due to the success of vaccine programs. As vaccine preventable diseases become far less common, parents, patients, and health care professionals have little firsthand familiarity with the effects of the disease, and over time the risks of vaccination, both known and alleged, become more visible.²

A second theme is the close association between promotion of vaccines and development of mandatory vaccine policies to ensure compliance. The most notable of these is mandatory vaccinations for school attendance, with critics arguing that these requirements interfere with individual autonomy.²

Proponents of mandatory vaccination argue it is ethically justified. Failure to vaccinate puts the unvaccinated individual at risk, as well as anyone they encounter, including those who are too young to be vaccinated or unable to be vaccinated for medical reasons.³ When it comes to vaccine mandates for children, vaccine mandates act to prevent parents from making decisions that unnecessarily expose them to the risk of infectious disease, akin to legally requiring children are secured in appropriate car seats.³ As stated in the 1905 Supreme Court case Jacobson v Massachusetts that upheld the right of state to enact vaccine mandates, “there are manifold restraints to which every person is necessarily subject for the common good.” ³

Role of the Internet

The internet has been transformative in bringing together those who criticize vaccines and vaccine policy, allowing for more rapid comparison of experiences, exchange of theories, and coordination of activism. There has been a massive growth in venues available for the publication of scientific research, and patients researching health topics may have trouble distinguishing reputable sources from those that are less trustworthy.² That being said, the often cited, now-retracted, 1998 paper by Wakefield et al on vaccines and autism appeared in The Lancet, demonstrating that the rigors of the traditional publication process is not without flaws.²

The speed that information can travel online makes it difficult to combat claims against the safety and necessity of vaccines as hypotheses often appear more quickly than they can be conclusively refuted. For example, as evidence mounted against a link between autism and the measles-mumps-rubella vaccine, replacement theories began to circulate against specific vaccine components and the timing of vaccines.²

Strategies for Responding to Vaccine Hesitancy

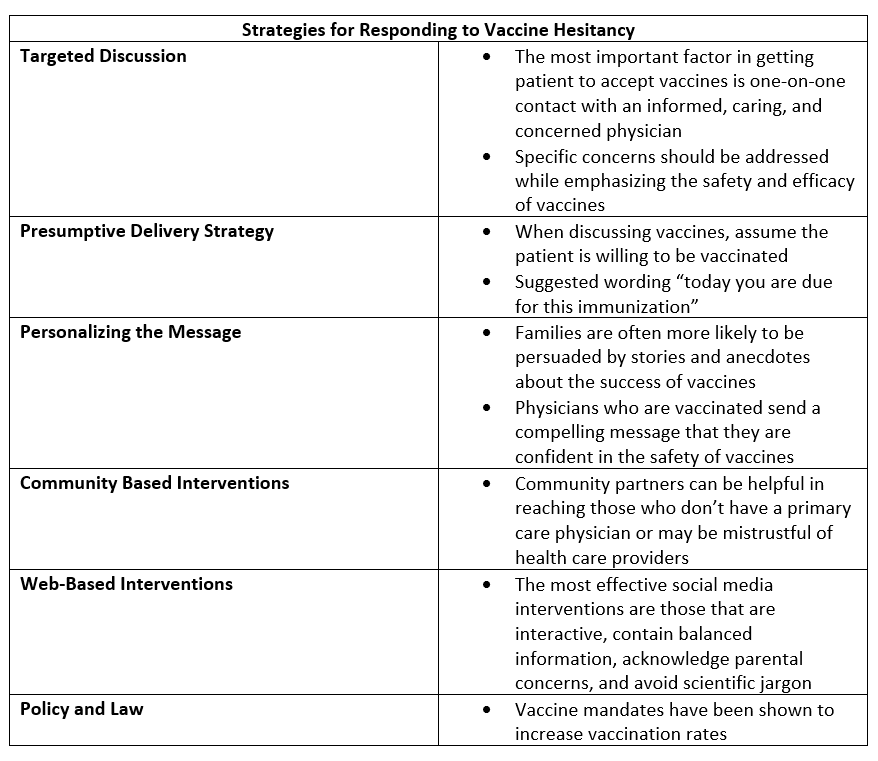

Targeted Discussion

Studies have shown that the most important factor in getting patient to accept vaccines is one-on-one contact with an informed, caring, and concerned physician.¹ It is important to have a nonconfrontational dialog with family while listening to and acknowledging their concerns while correcting any misconceptions.

Specific concerns and questions about vaccines and their components should be addressed. For example, those concerned about the presence of mercury (thimerosal) or aluminum may be reassured by providing evidence for the necessity for their use in some preparation of vaccines and lack of evidence of toxicity.¹

When discussing specific concerns, it’s okay not to know all the answers at the time of the original visit, telling a family you have not encountered this question before and will get back to them allows for them to feel heard and the conversation to continue. The Center for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) has information on specific vaccines that can be helpful when discussing with families.

In addition, strongly supporting the benefits of vaccination has an enormous influence on vaccine acceptance.¹ Sometimes it can be as easy as telling families that vaccines are save, effective, and save lives.

Presumptive Delivery Strategy

When discussing vaccines, how you phrase the discussion matters. Research has shown that patients are more likely to accept vaccines when a presumptive delivery strategy is used.¹ When using this strategy, the provider assumes patients will choose to vaccinate, and uses language that reflects that as opposed to asking patients about their vaccination plans. When using this approach, a provider may say “you are due for the flu shot today,” as opposed to “have you considered getting your flu shot today?”

Personalizing the Message

Families are often more likely to be persuaded by stories and anecdotes about the success of vaccines than simply reading numbers.¹ This can be especially helpful when discussing vaccines for illnesses that have become less prevalent and families may not be as familiar with the illness they protect against.

In addition, physicians stating that they are immunized as well as their children or grandchildren provide a compelling message that they are confident in the safety of vaccines.¹

Community Based Interventions

Community partnerships including education events and telephone reminders about immunizations have been shown to improve immunization rates, especially among families that do not have a primary care physician.³ Partnering with organizations that have long-standing relationships with the community can help get information about vaccines to communities that may be distrustful of healthcare providers.

Web-Based Interventions

The internet has demonstrated how easy it is to spread misinformation, but it can be used to educate as well. Presenting vaccine information through websites and social media has shown to improve attitudes around vaccines.³ While designing a website can be resource heavy and time consuming, individual providers can easily begin disseminating messages on their personal social media platforms. The most effective social media interventions are those that are interactive, contain balanced information, acknowledge parental concerns, and avoid scientific jargon.⁴

Policy and Law

Requiring vaccination for school attendance has been associated with increased vaccination rates among pediatric and adolescent patients.³ However, various states allow medical, religious, and personal belief exemptions for vaccinations, and rates of non-medical exemption are higher in states with easier policies for obtaining exemptions.³

Final Thoughts

Combating vaccine hesitancy is an important part of clinical practice, and a clear message that vaccines are safe and effective should be communicated. There are multiple strategies to address vaccine hesitancy in clinical practice and the community. While these conversations may be difficult at times, it is important to keep in mind that most vaccine-hesitant patients and families may not be opposed to vaccination but rather seeking information about the issues involved.

For more information on addressing vaccine hesitancy:

American Academy of Pediatrics Immunization Campaign Toolkit

Center for Disease Control and Prevention Immunization Toolkit

Elizabeth Lehto, D.O.

University of Louisville | UL · Department of Pediatrics | Doctor of Pediatric Emergency Medicine

Dr. Elizabeth Lehto is a Pediatric Emergency Medicine Attending at Norton Womens and Children’s Hospital. Dr. Lehto attended Midwestern University Arizona College of Osteopathic Medicine and completed her residency and fellowship at the University of Louisville.

References

Edwards KM, Hackell JM. Countering Vaccine Hesitancy. Pediatrics. 2016;138(3).

Schwartz JL. New media, old messages: themes in the history of vaccine hesitancy and refusal. Virtual Mentor. 2012;14(1):50-55.

Cataldi JR, Kerns ME, O'Leary ST. Evidence-based strategies to increase vaccination uptake: a review. Curr Opin Pediatr. 2020;32(1):151-159.

Puri N, Coomes EA, Haghbayan H, Gunaratne K. Social media and vaccine hesitancy: new updates for the era of COVID-19 and globalized infectious diseases. Hum Vaccin Immunother. 2020;16(11):2586-2593.

Cataldi JR, Kerns ME, O'Leary ST. Evidence-based strategies to increase vaccination uptake: a review. Curr Opin Pediatr. 2020;32(1):151-159.

Puri N, Coomes EA, Haghbayan H, Gunaratne K. Social media and vaccine hesitancy: new updates for the era of COVID-19 and globalized infectious diseases. Hum Vaccin Immunother. 2020;16(11):2586-2593.

Attwell K, Navin MC, Lopalco PL, Jestin C, Reiter S, Omer SB. Recent vaccine mandates in the United States, Europe and Australia: A comparative study. Vaccine. 2018;36(48):7377-7384.