How Would You/Could You Treat an Acute PE?

Dr. Sruti Brahmandam & Dr. Sravya Brahmandam

Introduction:

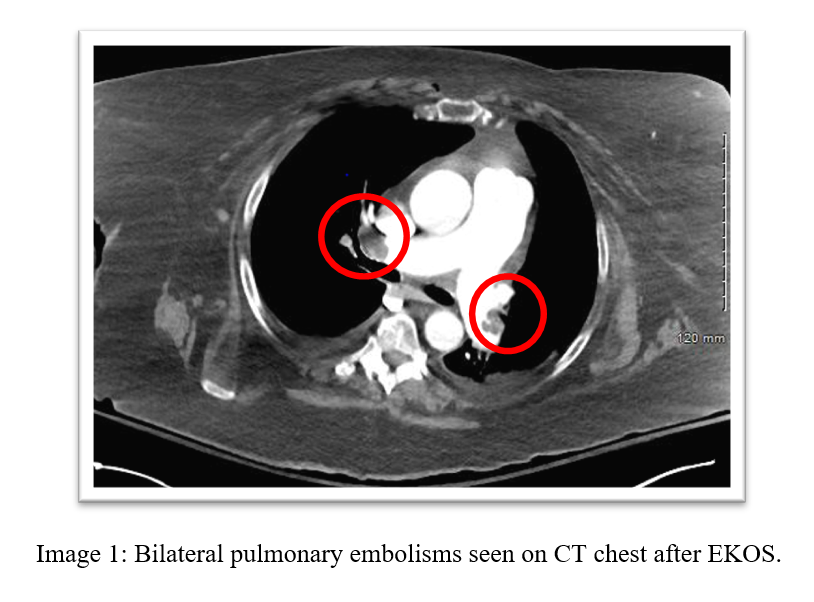

A 72-year-old female with history of OSA, recent tibula & fibular fracture s/p ORIF presents to the hospital with shortness of breath and was found to have bilateral submassive pulmonary embolisms and underwent EKOS thrombolysis and was discharged with Eliquis.

She returns to the hospital within 24 hours after a slip from bed with a left ankle dislocation. In the OR she had a cardiac arrest with return of spontaneous circulation. In the ICU, she was given systemic alteplase for worsening right heart strain and started on a heparin drip. As a result, obstructive shock greatly improved. Transthoracic echocardiogram demonstrated mod-severe global right ventricular hypokinesis and flattened septum with EF of 40%. She was eventually extubated and was discharged home.

Imaging:

Question:

What would you have done if this patient initially presented to you with a submassive pulmonary embolism and right heart strain?

a. Heparin drip

b. Catheter Directed Therapy

c. Systemic thrombolytics

Treatment of “Submassive PE” has always been a controversial topic. It is important to note that in 2019 the ESC guidelines changed the nomenclature in how to classify acute PE. Let’s take a look at these new classifications.

Part of this change is to help delineate the intermediate PE’s and allow clinicians to select the appropriate therapy. Now looking at these three options: several studies have looked at the role of systemic thrombolysis such as MAPPET-3 (2002), PEITHO Trial (2014), MOPPETT (2013), and UPETSG (1970) account for 74% of the patients evaluated. A Meta-analysis by Chatterjee in 2014 looked at several of the above studies to assess if the addition of thrombolysis to anticoagulation compared to anticoagulation alone affects mortality and bleeding complications.

Systemic Thrombolytics

The PEITHO Trial in 2014 looked at 1006 patients with a normal systolic blood pressure and both right ventricular dysfunction and elevated troponin were randomized with either heparin and tenecteplase or placebo and heparin.

The primary outcome was to look at death from any cause of hemodynamic decompensation.

Results showed a benefit with tenecteplase, but it came at the expense of increased major bleeding.

MAPPET-3 Trial was a randomized, double-blind study where 256 patients were randomized to receive 100 mg alteplase + heparin (intervention group) or placebo + heparin (control group)

The primary outcome was in-hospital death or clinical deterioration.

Results showed thrombolysis decreased the risk for rescue thrombolysis but didn’t affect mortality or adverse events.

MOPETT Trial was a randomized unblended trial with 121 patients that either received low-dose alteplase or control.

The primary outcome was to assess pulmonary hypertension with several secondary outcomes including all-cause mortality, major/minor bleeding, length of stay.

Results showed low dose alteplase plus anticoagulation reduced incidence of pulmonary hypertension compared to control.

Chatterjee Meta-analysis Conclusion

Patients with PE, those hemodynamically stable, thrombolysis was associated with lower mortality and more major bleeding.

Patients ≤ 65 years had no increase in major bleeding with thrombolysis.

In the MOPETT and TOPCOAT studies, there were better long-term outcomes in regards to pulmonary hypertension.

Catheter Directed Therapy

Now what about catheter directed therapy? The SEATTLE-2 Trial was a single-arm prospective trial with 31 patients with massive PE and 119 patients with submassive PE. The primary outcome here was to assess the RV/LV ratio at 48 hours.

Patients were treated with catheter director therapy which decreased RV dilation and pulmonary hypertension with no cases of intracerebral hemorrhage.

However, benefits of this study came at an increased cost and hospital length of stay (8.8 days +/- 5). Similar results were seen in the PERFECT Trial in 2015 which looked at 101 patients with acute PE.

Bottom Line: Evidence for catheter directed therapy is single arm without comparison to systemic thrombolysis or placebo. It is more expensive and causes longer length of ICU stay; however, it may be an option in patients with increased risk of intracerebral hemorrhage or major bleeding.

Conclusion:

There are several options to treat intermediate risk acute PE. More head-to-head studies are needed to compare various treatment options. Based on the new classification criteria, this patient would be intermediate high risk due to her right ventricular strain and troponin elevation. This case is tricky, if it were me, given her high clot burden and right ventricular strain I would have considered half dose TPA!

Sruti Brahmandam, M.D.

Medical school: Northeast Ohio Medical School, Rootstown, OH

Residency: University of Louisville Hospital

About Sruti: Originally from Ohio and came to Louisville for residency. I have been enjoying the vibrant culture of Louisville, and I am excited to continue my training here. I love experimenting in the kitchen and hope to create new recipes. I also enjoy watching movies and spending time with my family.

Research interests: COPD, Ultrasound, Sleep, Lung Cancer, Health Disparities

Sravya Brahmandam, M.D.

Medical school: University of Toledo College of Medicine, Toledo, OH

Residency: Wright State University Affiliated Hospitals, Dayton, OH

About Sravya: Born in Illinois, brought up in Ohio, and now in Kentucky for fellowship. As a tennis player, one might find me with a tennis racket at nearby tennis courts. I enjoy watching sports especially tennis, basketball, and football. In my spare time, I thoroughly enjoy watching various language movies together with my family. I plan to improve my culinary skills while I do my fellowship at UofL.

Research interests: COPD, Sleep, Lung Cancer, Pulmonary Hypertension

References:

Chatterjee, Saurav et al. “Thrombolysis for pulmonary embolism and risk of all-cause mortality, major bleeding, and intracranial hemorrhage: a meta-analysis.” JAMA vol. 311,23 (2014): 2414-21. doi:10.1001/jama.2014.5990

Konstantinides, Stavros V et al. “2019 ESC Guidelines for the diagnosis and management of acute pulmonary embolism developed in collaboration with the European Respiratory Society (ERS).” European heart journal vol. 41,4 (2020): 543-603. doi:10.1093/eurheartj/ehz405.

Meyer, Guy et al. “Recent advances in the management of pulmonary embolism: focus on the critically ill patients.” Annals of intensive care vol. 6,1 (2016): 19. doi:10.1186/s13613-016-0122-z.