…And they have atrial fibrillation. Now what?

Dr. Jeff Spindel

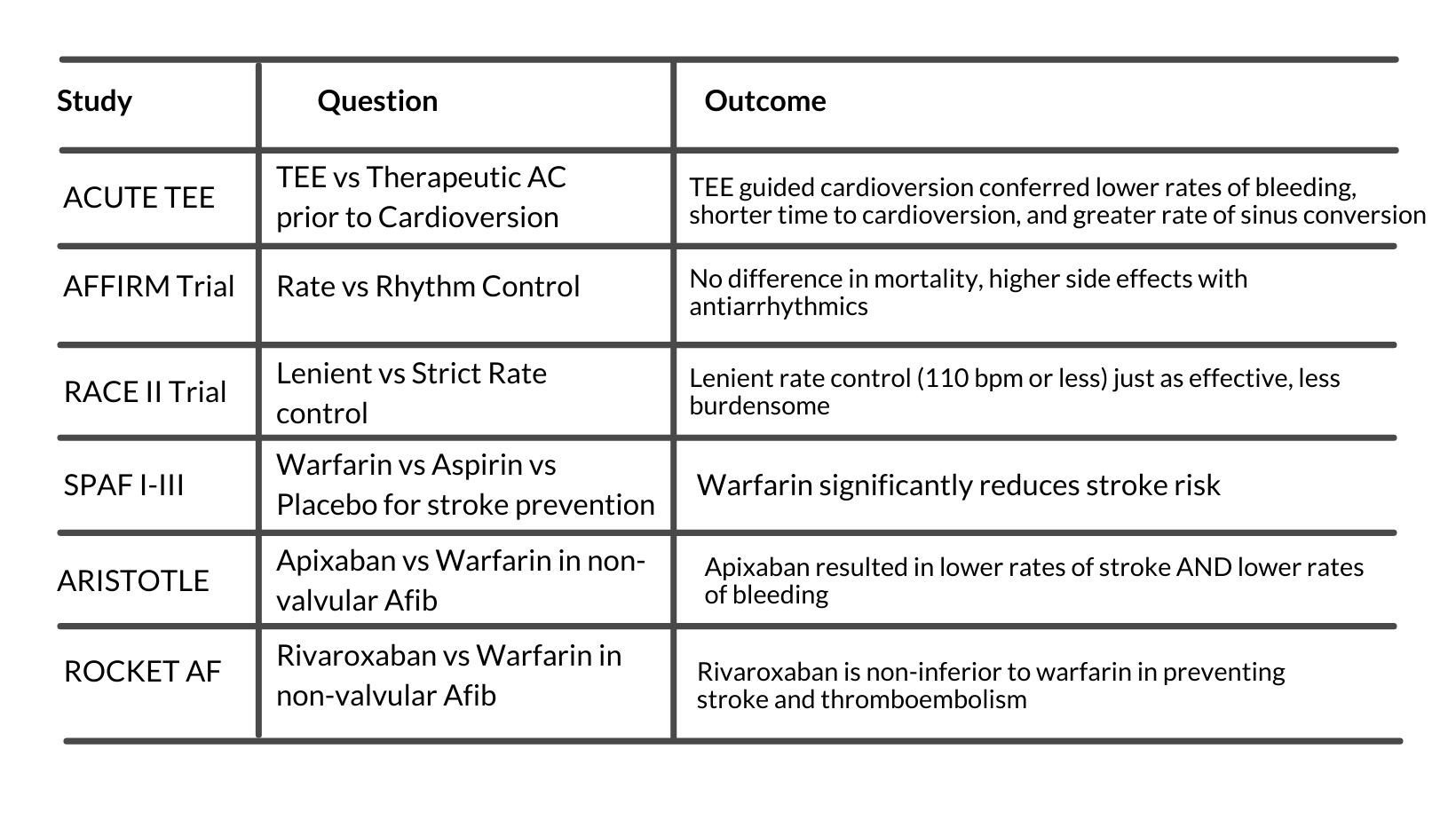

In this post we will discuss in-hospital management of patients with atrial fibrillation (Afib). We will cover new Afib and Afib with rapid ventricular response (RVR). We are going to focus on patients admitted to the general med-surg floors or progressive care unit. There are landmark randomized controlled trials that senior residents and providers should become familiar with. There will be cases at the end for each type of presentation above.

First, some definitions.

In general, atrial fibrillation will progress from paroxysmal to permanent, and at any given time, prevalence favors permanent Afib however incidence is higher of paroxysmal Afib. Rates of stroke increase with more time spent in atrial fibrillation. ¹

Second, some background information:

AFib is usually caused by underlying acute or chronic diseases. Risk factors include hypertension, valvular disease, pulmonary disease, especially obstructive sleep apnea, and heart failure.³-⁶ Potentially reversible causes of atrial fibrillation include hyperthyroidism and excessive alcohol intake.⁷ Disease processes that may exacerbate or uncover underlying Afib include infections, anemia, coronary artery disease, and kidney disease.⁸,⁹In any patient with new Afib, baseline testing involves an EKG to confirm diagnosis, echocardiogram to rule out valvular disease, heart failure, and atrial thrombi, and labwork.⁹

Therefore, in patients with newly diagnosed Afib:

Obtain EKG

Obtain echocardiogram

Obtain TSH, CBC, BMP/CMP

Workup for infection as indicated based on history and physical examination

In patients with an exacerbation of known Afib:

Treat the underlying illness to reduce burden and effects of Afib

Lastly, options for treatment.

1. Rhythm and rate control:

Afib can cause clinically significant reductions in cardiac output due to loss of the atrial kick and therefore reduced LV filling.¹⁰ Furthermore, Afib can cause heart failure through tachycardia-mediated cardiomyopathy, as proven in a large population in the Framingham Heart Study.¹¹

Both rate and rhythm control reduce or negate these long-term effects. First line rate control options include beta-blockers, non-DHP calcium channel blockers (Diltiazem, verapamil), and digoxin.¹² The first line rhythm control agent is amiodarone, which may have less of an effect of lowering blood pressure.⁹ Also important to note is that patients should not be started on rhythm control agents until atrial thrombi are ruled out as cardioversion in the presence of a thrombus may result in embolism.¹³ However, if the onset of Afib was felt by the patient, was recent (within 48 hours), and is the first occurrence, electrical cardioversion can be attempted without ruling out a thrombus.¹⁴

How do you choose between rhythm or rate control?

Based on the AFFIRM trial, there is no survival benefit of rhythm control over rate control. But rhythm control confers a higher risk of adverse drug reactions and increased hospitalizations.¹⁵

In rate control, what is considered rate controlled?

The RACE II trial determined that overall mortality, hospitalizations, and many secondary outcomes were less when using “lenient” heart rate control (target of 110 beats per minute or less).¹⁶

Therefore:

Target rate control over rhythm control unless indicated on an individual basis

Heart rate targets are <110 bpm

First line rate control options are beta blockers and non-DHP CCBs

First line rhythm control agent is amiodarone

2. Anticoagulation:

Based on the SPAF studies (I-III), patients identified as moderate to high risk of thromboembolic events should be anticoagulated.¹⁷ CHA2DS2-VASc is the current optimal stratification tool to quantify stroke risk.¹⁸

CHA₂DS₂-VASc Score for Atrial Fibrillation Stroke Risk - MDCalc

HAS-BLED is the current optimal stratification tool to quantify major bleeding risk.¹⁹

The presence of valvular abnormalities limits anticoagulation options to heparin and warfarin, however, in the absence of significant valvular disease, novel oral anticoagulants (NOACs) may be used.⁹,²⁰ This data is continuously evolving and it is likely that NOACs will be approved for use in valvular Afib in the future.

Therefore:

Assess each patient for risk of major bleeding.

Anticoagulate any patient with a CHA2DS2-VASc > 2 after weighing risks/benefits

NOACs are easier to use; warfarin or heparin should be used in valvular Afib

Now lets move on to some cases.

Patient 1:

A 65-year-old man with past medical history diabetes mellitus type II, HTN, COPD, and HLD presents with a COPD exacerbation. He is admitted to the floor, put on 2L oxygen by nasal canula, started on steroids and azithromycin, and given albuterol and ipratropium nebs Q6 hours. On telemetry the next morning, you see that his rhythm is atrial fibrillation with rate of 100 bpm and he currently denies palpitations or chest pain.

While the arrhythmia can likely be attributed to an exacerbation of his pulmonary disease, coupled with treatment with beta agonists, the workup should not stop there. Firstly, an EKG should be performed to confirm that this patient isn’t just throwing PACs. General lab work should be performed if not already done, as should a chest x-ray. Lastly, an echocardiogram should be performed. In this patient, an echo does two things: 1) determine if an atrial thrombus is present, and 2) determine if heart failure has caused Afib and vice versa. It is important to note that while a transthoracic echocardiogram (TTE) is generally the first test performed, the sensitivity for LA thrombus is poor and transesophageal echo (TEE) may be necessary.²¹

Treatment will be focused on rate control. Rhythm control should not be attempted (if at all) until a thrombus has been ruled out as he could have been in Afib previously and not realized. Options include a cardioselective BB (due to Beta agonist treatment for COPD) or non-DHP CCB. This patient has a CHA2DS2-VASc of 2 (HTN, age), and should be anticoagulated with heparin, lovenox, or a NOAC.

Patient 2:

A 78 year old female with medical history of atrial fibrillation, nonobstructive coronary artery disease, and chronic kidney disease stage III was admitted to the hospital for a gastrointestinal bleed. At home, she takes metoprolol succinate 100 mg daily, apixaban 5 mg twice daily, atorvastatin 80 mg daily, and a baby aspirin. Initial labwork revealed a hemoglobin of 8.2 from a baseline of 12.0 and she will undergo colonoscopy tomorrow morning. Her heart rate is currently 140 bpm, blood pressure is stable at 120/84. She receives 5 mg IV metoprolol two times without control of her heart rate.

First, what to do with her anticoagulation? Since this patient has a significant GIB, the risks of AC outweigh the benefits and therapy should be held. Once she has stabilized, a reassessment of the risks and benefits should be performed, specific to this patient. Next, how should her heart rate be controlled? She has already received her home dose of metoprolol plus two additional IV doses without good control (goal <110). Diltiazem, a medicine previously thought to cause hypotension²² is an option. But since she has been anticoagulated in the recent past, it is very unlikely an atrial thrombus is present. Therefore, this patient is a good candidate for rhythm control with amiodarone, which should not impact cardiac output as much as other agents,⁹ until her anemia has improved.

Jeff Spindel, D.O.

University of Louisville | UL · Department of Medicine | Doctor of Osteopathic Medicine

Jeffrey Spindel is currently a resident in Internal Medicine at the University of Louisville. His current research and academic interests include the effects of blood glucose control on the incidence of major adverse cardiac events and utilization of low cost coronary artery calcium scoring for risk stratification in asymptomatic patients.

References:

Chiang C-E, Naditch-Brûlé L, Murin J, et al. Distribution and Risk Profile of Paroxysmal, Persistent, and Permanent Atrial Fibrillation in Routine Clinical Practice. Circulation: Arrhythmia and Electrophysiology. 2012;5(4):632-639. doi:10.1161/CIRCEP.112.970749

January CT, Wann LS, Alpert JS, et al. 2014 AHA/ACC/HRS guideline for the management of patients with atrial fibrillation: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on practice guidelines and the Heart Rhythm Society. Circulation. 2014;130(23):e199-267. doi:10.1161/CIR.0000000000000041

Krahn AD, Manfreda J, Tate RB, Mathewson FA, Cuddy TE. The natural history of atrial fibrillation: incidence, risk factors, and prognosis in the Manitoba Follow-Up Study. Am J Med. 1995;98(5):476-484. doi:10.1016/S0002-9343(99)80348-9

Diker E, Aydogdu S, Ozdemir M, et al. Prevalence and predictors of atrial fibrillation in rheumatic valvular heart disease. Am J Cardiol. 1996;77(1):96-98. doi:10.1016/s0002-9149(97)89145-x

Davidson E, Weinberger I, Rotenberg Z, Fuchs J, Agmon J. Atrial fibrillation. Cause and time of onset. Arch Intern Med. 1989;149(2):457-459. doi:10.1001/archinte.149.2.457

Santhanakrishnan R, Wang N, Larson MG, et al. Atrial Fibrillation Begets Heart Failure and Vice Versa: Temporal Associations and Differences in Preserved Versus Reduced Ejection Fraction. Circulation. 2016;133(5):484-492. doi:10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.115.018614

Krahn AD, Klein GJ, Kerr CR, et al. How useful is thyroid function testing in patients with recent-onset atrial fibrillation? The Canadian Registry of Atrial Fibrillation Investigators. Arch Intern Med. 1996;156(19):2221-2224.

Klein Klouwenberg PMC, Frencken JF, Kuipers S, et al. Incidence, Predictors, and Outcomes of New-Onset Atrial Fibrillation in Critically Ill Patients with Sepsis. A Cohort Study. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2017;195(2):205-211. doi:10.1164/rccm.201603-0618OC

European Heart Rhythm Association, European Association for Cardio-Thoracic Surgery, Camm AJ, et al. Guidelines for the management of atrial fibrillation: the Task Force for the Management of Atrial Fibrillation of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC). Eur Heart J. 2010;31(19):2369-2429. doi:10.1093/eurheartj/ehq278

Rodman T, Pastor BH, Figueroa W. Effect on cardiac output of conversion from atrial fibrillation to normal sinus mechanism. Am J Med. 1966;41(2):249-258. doi:10.1016/0002-9343(66)90020-9

Wang TJ, Larson MG, Levy D, et al. Temporal relations of atrial fibrillation and congestive heart failure and their joint influence on mortality: the Framingham Heart Study. Circulation. 2003;107(23):2920-2925. doi:10.1161/01.CIR.0000072767.89944.6E

Chao T-F, Liu C-J, Tuan T-C, et al. Rate-control treatment and mortality in atrial fibrillation. Circulation. 2015;132(17):1604-1612. doi:10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.114.013709

Lurie A, Wang J, Hinnegan KJ, et al. Prevalence of Left Atrial Thrombus in Anticoagulated Patients With Atrial Fibrillation. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2021;77(23):2875-2886. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2021.04.036

Stiell IG, Clement CM, Rowe BH, et al. Outcomes for Emergency Department Patients With Recent-Onset Atrial Fibrillation and Flutter Treated in Canadian Hospitals. Ann Emerg Med. 2017;69(5):562-571.e2. doi:10.1016/j.annemergmed.2016.10.013

A Comparison of Rate Control and Rhythm Control in Patients with Atrial Fibrillation. New England Journal of Medicine. 2002;347(23):1825-1833. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa021328

Van Gelder IC, Groenveld HF, Crijns HJGM, et al. Lenient versus Strict Rate Control in Patients with Atrial Fibrillation. New England Journal of Medicine. 2010;362(15):1363-1373. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1001337

Boston Area Anticoagulation Trial for Atrial Fibrillation Investigators, Singer DE, Hughes RA, et al. The effect of low-dose warfarin on the risk of stroke in patients with nonrheumatic atrial fibrillation. N Engl J Med. 1990;323(22):1505-1511. doi:10.1056/NEJM199011293232201

Lip GYH, Nieuwlaat R, Pisters R, Lane DA, Crijns HJGM. Refining clinical risk stratification for predicting stroke and thromboembolism in atrial fibrillation using a novel risk factor-based approach: the euro heart survey on atrial fibrillation. Chest. 2010;137(2):263-272. doi:10.1378/chest.09-1584

Pisters R, Lane DA, Nieuwlaat R, de Vos CB, Crijns HJGM, Lip GYH. A novel user-friendly score (HAS-BLED) to assess 1-year risk of major bleeding in patients with atrial fibrillation: the Euro Heart Survey. Chest. 2010;138(5):1093-1100. doi:10.1378/chest.10-0134

Caturano A, Galiero R, Pafundi PC. Atrial Fibrillation and Stroke. A Review on the Use of Vitamin K Antagonists and Novel Oral Anticoagulants. Medicina (Kaunas). 2019;55(10). doi:10.3390/medicina55100617

Turhan S, Ozcan OU, Erol C. Imaging of intracardiac thrombus. Cor et Vasa. 2013;55(2):e176-e183. doi:10.1016/j.crvasa.2013.02.005

Hirschy R, Ackerbauer KA, Peksa GD, O’Donnell EP, DeMott JM. Metoprolol vs. diltiazem in the acute management of atrial fibrillation in patients with heart failure with reduced ejection fraction. Am J Emerg Med. 2019;37(1):80-84. doi:10.1016/j.ajem.2018.04.062