IS IT A STEMI? ST-ELEVATION MYOCARDIAL INFARCTION AND ITS EQUIVALENTS

Dr. Aaron Kuzel

Case

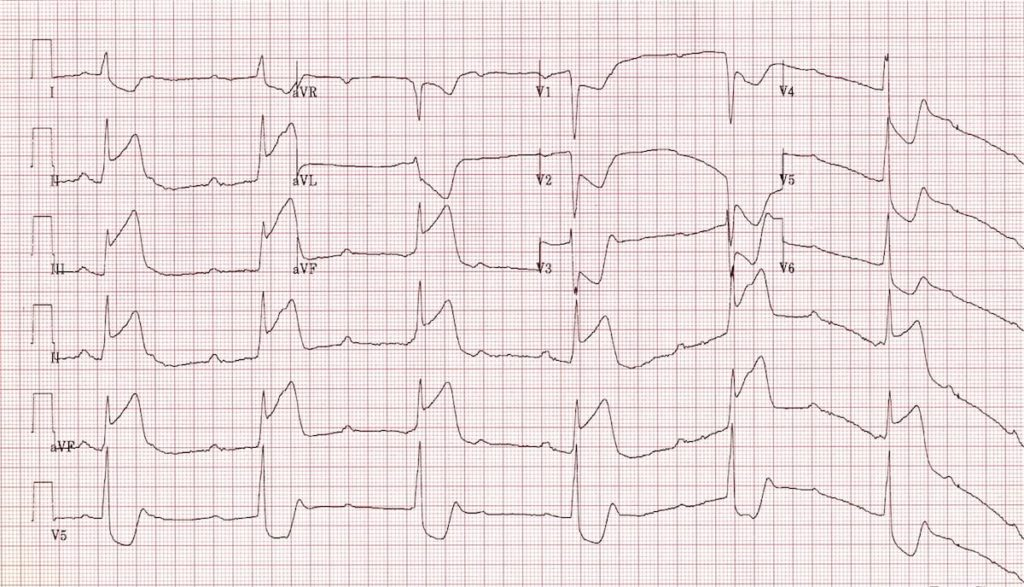

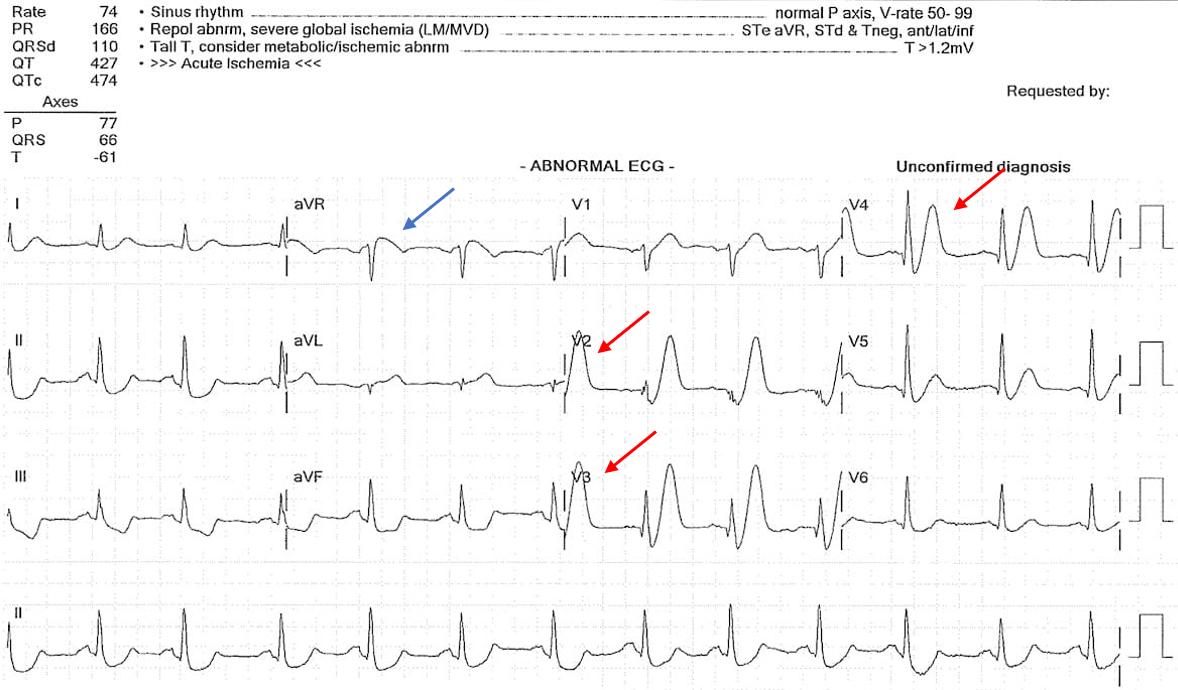

50-year-old male with a history of hypertension, hyperlipidemia, and two pack-per-day tobacco use history presents to the emergency department for sudden onset of crushing chest pain and pressure. The patient states the pain started while watching television at home and that the pain radiates down his right arm. He denies any shortness of breath, nausea, vomiting, or abdominal pain. Emergency medical services (EMS) provided the patient 324 mg Aspirin. EMS transported the patient to the nearest hospital with Percutaneous Coronary Intervention (PCI) capacity. EMS transmitted the following EKG:

Acute Coronary Syndrome

Acute Coronary Syndrome or ACS is any condition that results in ischemia of the coronary arteries resulting in diminished perfusion of the myocardial tissue. There is a spectrum of cardiac diseases that fall into the designation of ACS including: ST-Elevation Myocardial Infarction (STEMI), non-STEMI (NSTEMI), and unstable angina. This discussion will center around STEMIs as well as introduce some STEMI-equivalents.

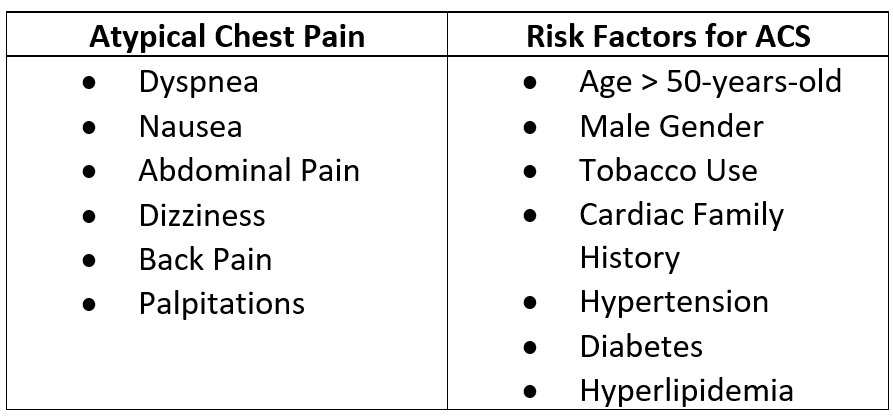

Chest pain is the most common presenting symptoms for ACS. However, 20-30% of patients presenting with ACS will present with atypical symptoms. There are associated risk factors for ACS as noted in the table below.

Work-Up and Management

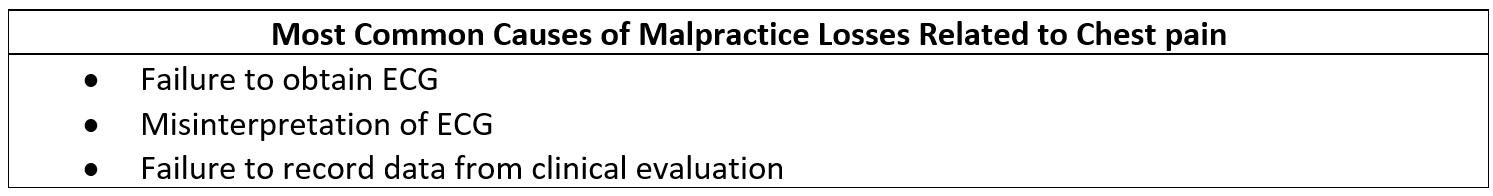

Patients presenting with concern for ACS should receive prompt electrocardiography (ECG) as well as CBC, chest radiograph, electrolytes, serum troponin, and PT/PTT. The 2013 American College of Cardiology (ACC) and American Heart Association (AHA) guidelines recommend serial ECGs in the first hour if there are concerning symptoms and the first ECG is non-diagnostic. The serial ECGs are important as approximately 15-20% of STEMIs are diagnosed on the repeat ECG. Missing a STEMI or myocardial infarction is one of the most common causes of malpractice for the emergency physician. The table below demonstrates the most common causes of losses in malpractice cases related to the cause of chest pain.

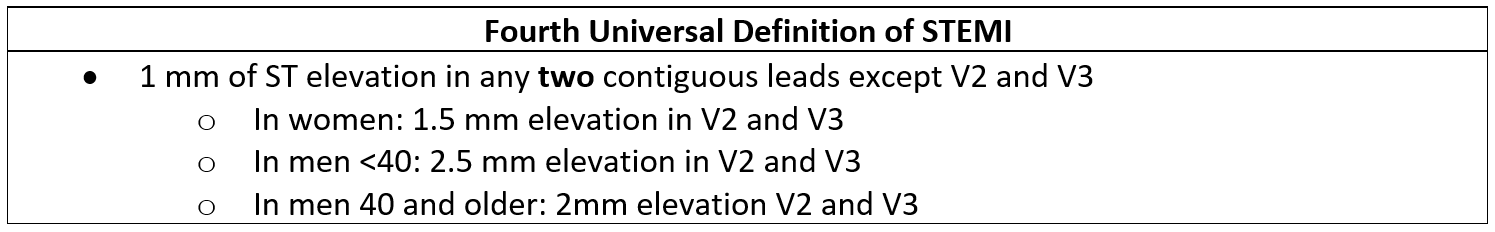

Definition of a STEMI

ST-segment elevations are noted with the red arrows. Notice that there are ST-segment elevations in three contiguous leads: II, III, and AVF. There is usually reciprocal ST-segment depression in the opposite leads associated with ST-elevation myocardial infarctions. In this case of an Inferior Myocardial Infarction, there are reciprocal ST-segment depressions in the Septal and Lateral leads. This is denoted with blue arrows.

Wellens Syndrome

Wellens Syndrome refers to angina associated with T wave inversions in the left anterior descending coronary artery or LAD most notably in leads V2 and V3. Wellens Syndrome often presents in a pain-free state, but those patients who did not undergo reperfusion therapy with Wellens Syndrome noted on the ECG fared poorly with 75% developing an anterior wall myocardial infarction due to proximal LAD occlusion. Patients diagnosed with Wellens Syndrome should proceed urgently to cardiac catheterization.

There are two types of Wellens Syndrome:

Type A is a biphasic T wave in V2 and V3 occurring in 25% of cases and Type B are deep, symmetrically inverted T-waves in V2 and V3 occurring in 75% of cases.

Life in the Fast Lane

https://litfl.com/st-segment-ecg-library/

De Winter’s T Waves

De Winter’s T waves were first identified in 2008 and account for 2% of proximal LAD occlusions making it a STEMI-equivalent requiring emergent cardiac catheterization. De Winter’s T waves are tall, peaked T waves in the precordial leads (V1-V6) with ST-segment depression at the J-point. In most cases, ST-segment elevation will be seen in lead aVR, however this is not specific.

Life in the Fast Lane

https://litfl.com/st-segment-ecg-library/

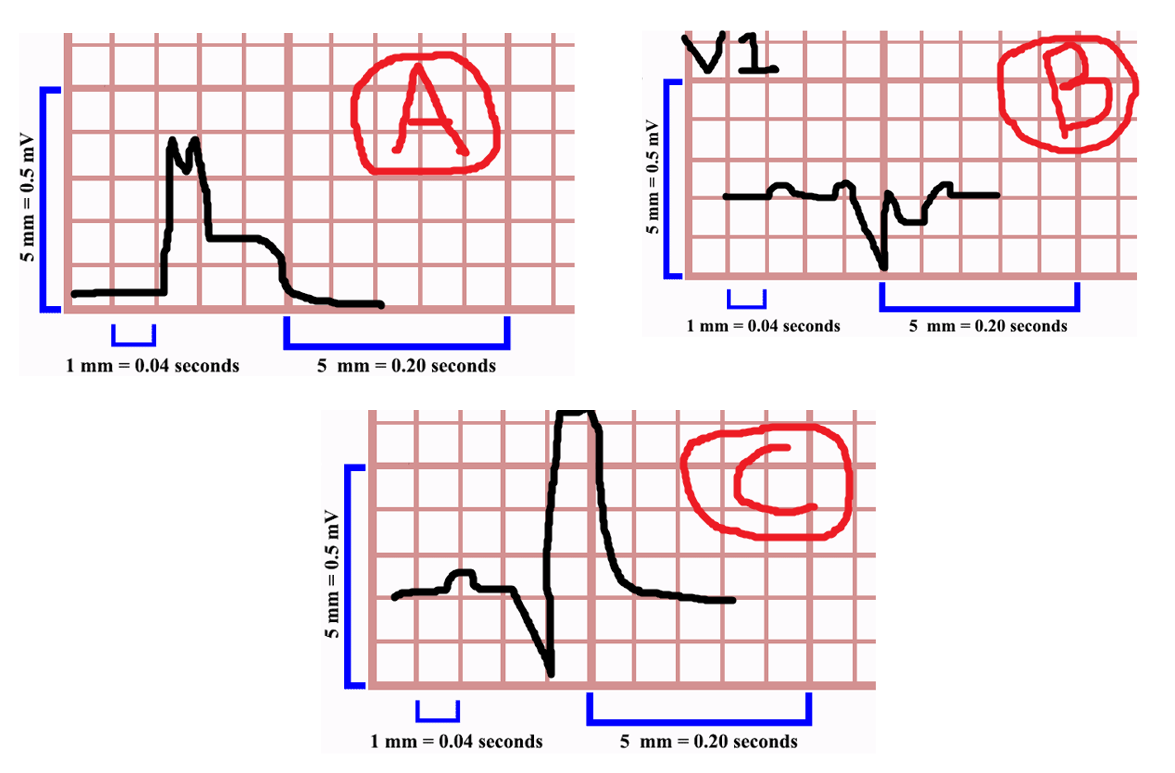

Left Bundle Branch Block with Myocardial Infarction

Previously, a new Left Bundle Branch Block (LBBB) was considered a STEMI-equivalent, however, recent literature suggests that a new LBBB does not often demonstrate increased risk of acute myocardial infarction. However, in 1996, Dr. Sgarbossa published a study of acute myocardial infarction in the presence of a LBBB with three criteria. Although the Sgarbossa criteria is not very sensitive, the findings were very specific for the finding of acute myocardial infarction.

Dr. Amal Mattu, professor of emergency medicine from the University of Maryland, separates the Sgarbossa criteria into three subsections: Category A, B, and C.

In Sgarbossa A, the QRS complex is deflected in the positive direction (up) and ST-segment elevation is also present or concordance. If this occurs in any lead in the presence of a LBBB this is a STEMI-equivalent and the patient should proceed to cardiac catheterization. In Sgarbossa B, the QRS complex is deflected in the negative direction as well as the ST-Segment depression a shown in the example above in V1. If the ST segment is depressed in V1, V2, or V3 and the QRS complex is deflected downward this is also a STEMI-equivalent indicating acute myocardial infarction in the presence of a LBBB. Finally, in Sgarbossa C if the ST segment elevation is greater than 5 mm (or 5 blocks), this may indicate a STEMI-equivalent, however this is not as specific as criteria A or B. That being said, the finding of Sgarbossa C should prompt the physician to consult Interventional Cardiology as well as consider other signs and symptoms of ischemia.

Sgarbossa A:

Life in the Fast Lane

https://litfl.com/sgarbossa-criteria-ecg-library/

In the above example, there is ST elevation concordance with the QRS in the presence of a LBBB in lead aVL indicating a myocardial infarction. Notice, that this is the only lead with ST-elevation >1 mm, but the criteria indicates that concordant ST-segment elevation in any lead with a LBBB is an indication for PCI.

Life in the Fast Lane

https://litfl.com/sgarbossa-criteria-ecg-library/

In this example, there is concordant ST-depression in lead V2 in the presence of a LBBB indicating the need for emergent cardiac catherization.

Back to the Case:

The patient presented to a PCI center and was taken immediately to the cath lab for PCI given the findings of an Inferior Myocardial Infarction. The patient was found to have 100% Right Coronary Artery occlusion as well as a right ventricle infarction. He tolerated the procedure well and was discharged from the hospital a few days later on a new regimen of aspirin, statin, and anti-platelet therapy.

Right Ventricular Infarction:

Right ventricular infarction can be found in approximately 40% of all inferior STEMIs and patients afflicted with such conditions are considered preload sensitive. As patients are preload sensitive, they are susceptible to severe hypotension when using nitrates or other medications that can reduce preload. Nitroglycerin, typically indicated in cardiac chest pain, are contraindicated in patients with inferior STEMIs due to their likelihood in worsening right ventricular contractility. Patients presenting with such symptoms should be treated with intravenous fluids in order to increase preload and improve right ventricular contractility.

Detection of right ventricular infarctions are sometimes difficult to diagnose on ECGs. The easiest way to diagnose right ventricular infarction is using lead V4R. This lead is obtained by placing the V4 electrode on the right 5th intercostal space over the midclavicular line. If the V4R demonstrates ST elevation in concordance with ST elevation in leads II, III, and AVF it is likely diagnostic of right ventricular infarction. The use of lead V4R in the diagnosis of right ventricular infarction is 88% sensitivity.

Conclusion:

There are many findings on ECG that could indicate either a STEMI, STEMI-equivalent, or the presence of ischemia. It is important to note that there are a multitude of other ischemic rhythms and this is a brief and limited introduction to ischemic ECGs. Ischemia can be present even in the absence of ECG changes or changes in troponin, so history and physical still remain the most important methods in physician diagnosis of myocardial infarction and ischemia.

For further reading:

Electrocardiography in Emergency Medicine by Amal Mattu, Jeffrey Tabas, and Robert Barish

ECGs for the Emergency Physician Volume 1 and Volume 2 by Amal Mattu and William Brady

Electrocardiography in Emergency, Acute, and Critical Care by Amal Mattu Jeffrey Tabas and William Brady

Aaron R. Kuzel,

DO, MBA

University of Louisville | UL · Department of Emergency Medicine

Dr. Aaron Kuzel is a resident at the University of Louisville School of Medicine. He attended the Lincoln Memorial University DeBusk College of Osteopathic Medicine for medical school.

References:

AHA ACA - NSTEMI ACS Guidelines 2014

de Winter R, et al. A new ECG sign of proximal LAD occlusion. NEJM. 2008; 359:2071–2073.

de Zwaan C, Bär FW, Wellens HJ. Characteristic electrocardiographic pattern indicating a critical stenosis high in left anterior descending coronary artery in patients admitted because of impending myocardial infarction. Am Heart J. 1982;103(4 Pt 2):730-736.

Hennings JR and Fesmire FM. A new electrocardiographic criteria for emergent reperfusion therapy. Am J Emerg Med. 2012; 30(6):994–1000.

Lee TH, Goldman L. Evaluation of the patient with acute chest pain. N Engl J Med. 2000 Apr 20;342(16):1187-95.

Maloy KR, Bhat R, Davis J, et al. Sgarbossa Criteria are highly specific for acute myocardial infarction with pacemakers. West J Emerg Med. 2010;11(4):354-357. (Retrospective cohort; 57 patients)

Pope JH, Aufderheide TP, Ruthazer R, Woolard RH, Feldman JA, Beshansky JR, Griffith JL, Selker HP. Missed diagnoses of acute cardiac ischemia in the emergency department. N Engl J Med. 2000 Apr 20;342(16):1163-70.

Sgarbossa EB, Pinski SL, Barbagelata MD, et al. Electrocardiographic Diagnosis of Evolving Acute Myocardial Infarction in the Presence of Left Bundle-Branch Block. NEJM. 1996;334(8)

Thygesen, K et al. Fourth Universal Definition of Myocardial Infarction (2018). 2018 Nov 13;138(20):e618-e651.

Ünlüer EE et al. Red Flags in Electrocardiogram for Emergency Physicians: Remembering Wellens' Syndrome and Upright T wave in V1. West J Emerg Med. 2012 May; 13(2): 160–162