Microaggressions

Dr. Elizabeth Lehto

A female physician finishes a patient encounter, only to be asked when the doctor will be in. A black medical student enters a patient room, the patient asks why she didn’t arrive to empty the trash sooner. These are just two of many situations when people’s biases reveal themselves in a way that makes others feel uncomfortable and insulted, also known as a microaggression.

What Are Microaggressions?

Microaggressions are brief verbal or behavioral indignities against marginalized groups. They may be intentional or unintentional and are often indirect or subtle. They are frequently unconsciously delivered in the form of subtle dismissive looks, gestures, and tones. Those who engage in microaggressions may not be aware how their words and actions discriminate against others.¹ It is important to keep in mind, that the term “micro” refers to these exchanges being commonplace, not that they are insignificant.² In fact, these interactions can take a real toll on the mental health of their recipients and can make a work or learning environment more hostile.

Regular exposure to perceived discrimination of any kind adversely affects the psychological and physical health of the recipients. Repeat microaggressions have been linked to depression, anxiety, and hypertension. Additionally, racial and ethnic discrimination is an identifiable stressor that may play a role in health disparities.³

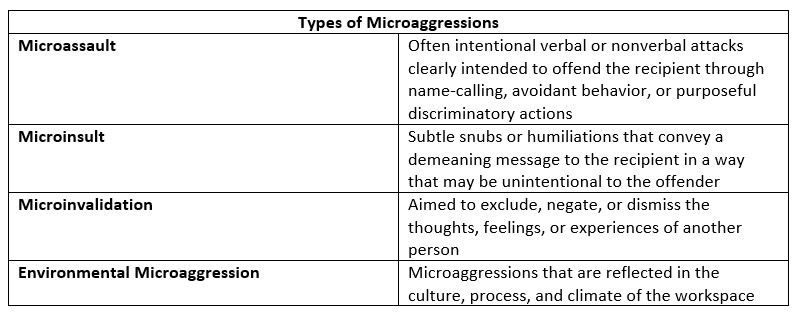

Types of Microaggressions

Microassault

Microassaults are the most blatant form of microaggression and are often intentional. They are characterized by verbal or nonverbal attacks clearly intended to offend the recipient through name-calling, avoidant behavior, or purposeful discriminatory actions.¹ Microassaults differ from blatant racism by focusing on an individual rather than the group, although racism may still be the motivation.³ Examples include comments such as “you people are all the same,” referring to someone as “colored,” discouraging interracial interactions, or refusal to work with a team member.³

Microinsult

Microinsults are subtle snubs or humiliations that convey a demeaning message to the recipient in a way that may be unintentional to the offender.³ These communications convey insensitivity and demean a person’s heritage or identity.¹ For example, complementing someone on how well they speak English sends the message that they are not American, or confusing a physician for a nonmedical role because they do not “look” like a physician. Microinsults can also occur nonverbally, such as when a coworker fails to acknowledge a woman speaking in a meeting, spending the message that her contributions are unimportant.¹

Microinvalidation

Microinvalidations are aimed to exclude, negate, or dismiss the thoughts, feelings, or experiences of another person. For example, when someone is sharing a story about experiencing racial discrimination and is told not to be overly sensitive, the experience is nullified and its importance invalidated.¹

Environmental Microaggression

Environmental microaggressions occur when microaggressions are reflected in the culture, process, and climate of the workspace. They commonly occur at the macrolevel and are reminders of the biases that exist at a systemic level. Examples include hallways being decorated with photographs of white male administrators that can lead to the sense of being “other” from those in power, or lack of rooms for breastfeeding mothers at a workplace can perpetuate the idea that women with families are unwelcome in the workplace.³

Responding to Microaggressions

Responding to microaggressions can be challenging. When responding to microaggressions from patients, providers must address the behavior while preserving a therapeutic alliance with the patient.⁴ Responding to microaggressions expressed by colleagues or senior physicians have the added complexity of hierarchy and threat of reprisal.⁴ The following strategies can be helpful when addressing microaggressions.

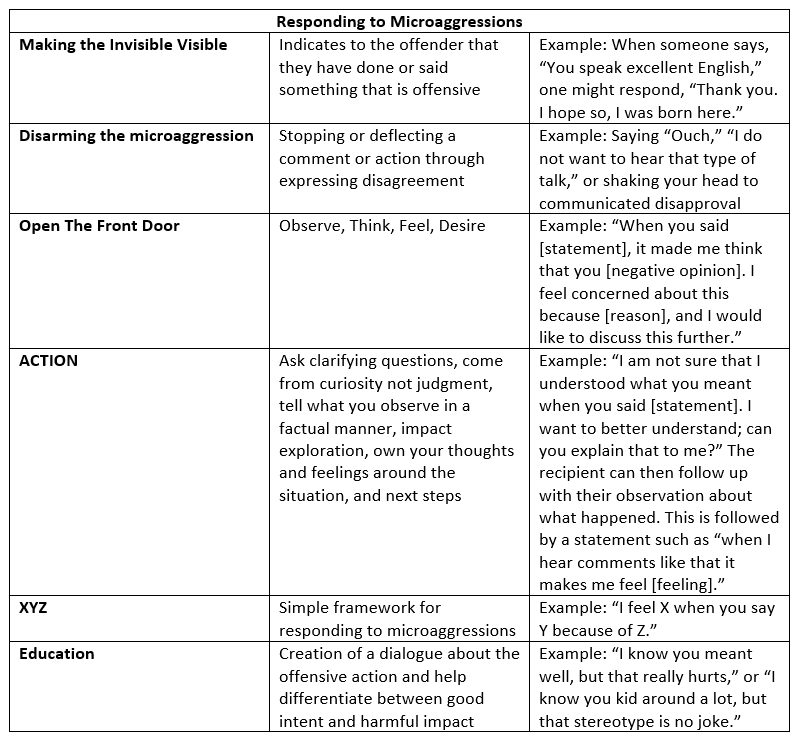

Making the Invisible Visible

Most perpetrators of microaggressions feel that their actions are devoid of bias and prejudice, which makes it hard to change the behavior. This strategy aims to indicate to the perpetrator that they have done or said something that is offensive. This can be done by verbally describing what is happening in a nonthreatening manner and allows the perpetrator to consider the impact and meaning of their actions or words. This has an even greater impact when someone in a position of power responds.⁵

For example, when someone says, “You speak excellent English,” one might respond, “Thank you. I hope so, I was born here.” This acknowledges the conscious complement of the perpetrator while undermining the unspoken assumption of being a foreigner. This can plant a seed of possible future awareness of false assumptions.⁵

Disarming the microaggression

A more direct method of addressing microaggressions is to disarm them by stopping or deflecting the comments or actions through expressing disagreement, challenging what was said, or pointing out its harmful impact.⁵

One technique is to state “Ouch!” in responds to a comment or action. This indicates that something said was offensive and can facilitate further conversation and exploration about biases.⁵

Another tactic is interrupting the communication and redirecting it. When a biased or misinformed statement is made, interrupt it and communicate your disagreement, for example saying, “I do not want to hear that type of talk,” or shaking your head to communicated disapproval.⁵

Open The Front Door

The “Open The Front Door” method for structuring a response to microaggressions stands for “Observe, Think, Feel, Desire.” The conversation is started by stating what is observed, how the comment was interpreted, how it made the recipient fell, and what the desired outcome might be.³

One example may be “When you said [statement], it made me think that you [negative opinion]. I feel concerned about this because [reason], and I would like to discuss this further.”³

ACTION

Another framework for responding to microaggressions is ACTION, which stands for ask clarifying questions, come from curiosity not judgment, tell what you observe in a factual manner, impact exploration, own your thoughts and feelings around the situation, and next steps.³

An example using this framework would be “I am not sure that I understood what you meant when you said [statement]. I want to better understand; can you explain that to me?” The recipient can then follow up with their observation about what happened. This is followed by a statement such as “when I hear comments like that it makes me feel [feeling].” The discussion can close with action items to follow up on.³

XYZ

The simplest framework for responding to microaggressions is the XYZ method: “I feel X when you say Y because of Z.”

Education

The ultimate hope is to educate those who engage in microaggressions by creating a dialog about the offensive action and what it says about their beliefs and values. Education is a long-term process, and while brief encounters don’t always allow opportunities for deep discussions, over the long run they can plant the seeds of change that may blossom in the future.⁵

One educational tactic is to help microaggressors differentiate between good intent and harmful impact. When microaggressions are pointed out, a common reaction is to become defensive and shift the focus from action to intention, for example stating, “I did not mean it that way.” It is often helpful to discuss impact instead of intent, such as saying, “I know you meant well, but that really hurts,” or “I know you kid around a lot, but that stereotype is no joke.”⁵

Practice Makes Perfect

Like other challenging but crucial conversations in the health care setting, responding to microaggressions is a skill honed with repetition, self-reflection, and deliberate practice. It can be helpful to practice saying the exact words you might use in a given situation through imagining specific scenarios and trying out the words you might say.4 Simulation has been shown to help increased confidence and preparedness in having these types of conversations among medical residents.6 In addition, some institutions offer training on having discussions about discrimination and responding to microaggressions.

Final Thoughts

While microaggressions are oftentimes unintentional, regular exposure to perceived discrimination of any kind adversely affects the psychological and physical health of the recipients. As these actions are often unintentional, it is important to respond to the act and educate the microaggressor. There are multiple methods of responding to microaggressions and practicing responses can be helpful. While some institutions offer training on addressing microaggressions, not all do. Developing workshops and simulations on responding to microaggressions may be beneficial to empower physicians and trainees.

For more information:

Recognizing Microaggressions and the Messages They Send https://academicaffairs.ucsc.edu/events/documents/Microaggressions_Examples_Arial_2014_11_12.pdf

Interrupting Microaggressions https://academicaffairs.ucsc.edu/events/documents/Microaggressions_InterruptHO_2014_11_182v5.pdf

Managing Microaggressions Webinar https://www.facs.org/member-services/surgeon-wellbeing/microaggressions-series

Elizabeth Lehto, D.O.

University of Louisville | UL · Department of Pediatrics | Doctor of Pediatric Emergency Medicine

Dr. Elizabeth Lehto is a Pediatric Emergency Medicine Attending at Norton Womens and Children’s Hospital. Dr. Lehto attended Midwestern University Arizona College of Osteopathic Medicine and completed her residency and fellowship at the University of Louisville.

REFERENCES:

Sue DW, Capodilupo CM, Torino GC, et al. Racial microaggressions in everyday life: implications for clinical practice. Am Psychol. 2007;62(4):271-286.

Molina MF, Landry AI, Chary AN, Burnett-Bowie SM. Addressing the Elephant in the Room: Microaggressions in Medicine. Ann Emerg Med. 2020;76(4):387-391.

Torres MB, Salles A, Cochran A. Recognizing and Reacting to Microaggressions in Medicine and Surgery. JAMA Surg. 2019;154(9):868-872.

Wheeler DJ, Zapata J, Davis D, Chou C. Twelve tips for responding to microaggressions and overt discrimination: When the patient offends the learner. Med Teach. 2019;41(10):1112-1117.

Sue DW, Alsaidi S, Awad MN, Glaeser E, Calle CZ, Mendez N. Disarming racial microaggressions: Microintervention strategies for targets, White allies, and bystanders. Am Psychol. 2019;74(1):128-142.

March C, Walker LW, Toto RL, Choi S, Reis EC, Dewar S. Experiential Communications Curriculum to Improve Resident Preparedness When Responding to Discriminatory Comments in the Workplace. J Grad Med Educ. 2018;10(3):306-310.