101: Acute Chest Discomfort

Dr. Pranav Pillai

Introduction

Remember all those times you are called from the ED for a chest pain evaluation and admission to CCU and you think inside your head, “Ha, another one of those false calls”; but on reviewing the chart, getting the history and physical examination, you’re not so sure anymore? Well, you are not alone. And that’s not a bad thing either.

Instead of chest pain, from now on, we shall describe it as chest discomfort. Because a lot of times, our patients will deny chest pain, but will endorse some kind of funny sensation, burning or dull discomfort which cannot rule out cardiac causes.

*Time to throw in some numbers to look smart* Chest discomfort is apparently the second most common complaint for ED visits in the US, as per CDC data, with 5.5 % of 1.3 million visits for the same.1 However, only 10-15 % of these patients actually have acute coronary syndrome (ACS). Does this mean we can relax? Not yet. The diagnosis of ACS is missed in approximately 2 % of these patients with severe fatal consequences on being mistakenly discharged: a 30-day risk of death that is double that of their hospitalized counterparts.

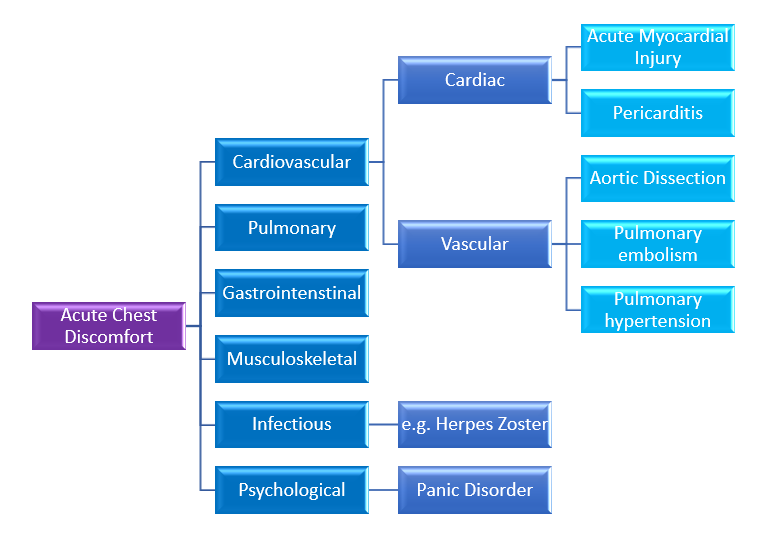

Causes of Acute Chest Discomfort

Let’s first try to understand the different causes and categorize them under broad headings.

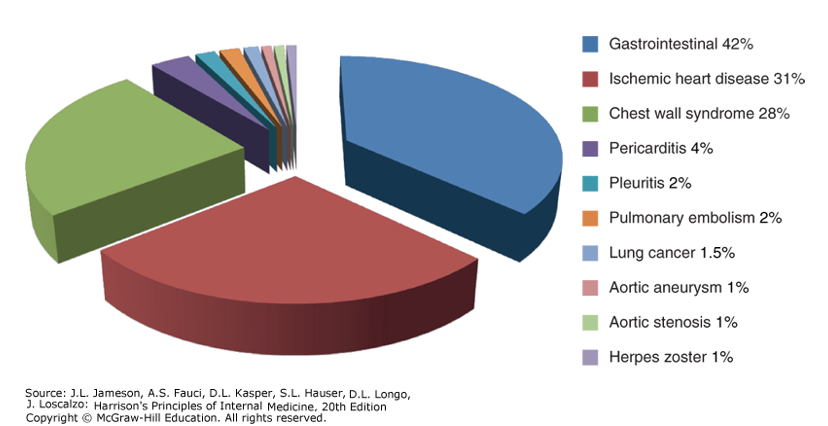

The most common diagnoses on discharge are usually gastrointestinal causes. The cardiopulmonary conditions that are life-threatening to the patient are ACS, aortic dissection, pulmonary embolism (PE), tension pneumothorax and pericarditis with tamponade, and esophageal rupture among non-cardiopulmonary causes, which is why it is important to get a good history, physical exam, labs and imaging to form a basic understanding of what could be the cause.

Figure 1: Distribution of final discharge diagnoses in patients with nontraumatic acute chest pain. (Figure prepared from data in P Fruergaard et al: Eur Heart J 17:1028, 1996.). Source: Chapter 11 Chest Discomfort. Jameson J, Fauci AS, Kasper DL, Hauser SL, Longo DL, Loscalzo J. Harrison's Principles of Internal Medicine, 20e; 2018.

Approach to the Patient

What takes utmost precedence is an initial evaluation of the patient’s clinical stability and the possibility that the clinical presentation may be driven by a life-threatening cause. Call it your Spidey sense or your “Peter tingle”, but if you feel something is not right, if the patient appears to be in severe pain or respiratory distress, get an electrocardiogram (EKG) right away.

History

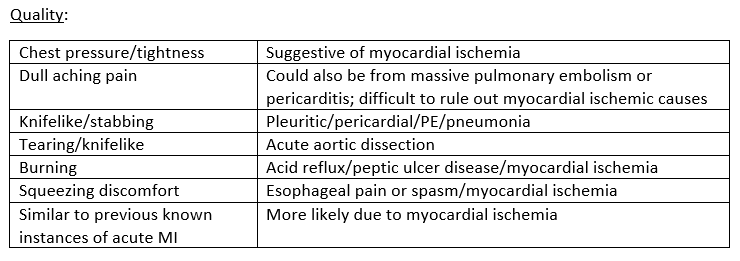

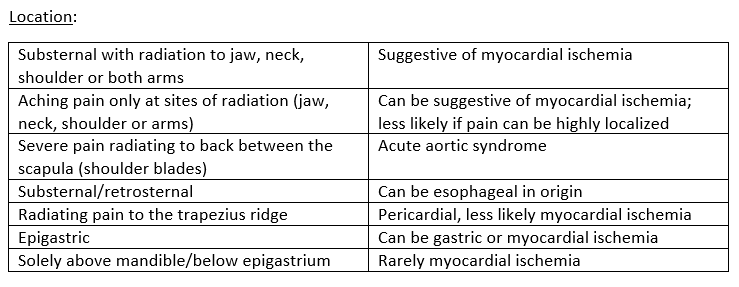

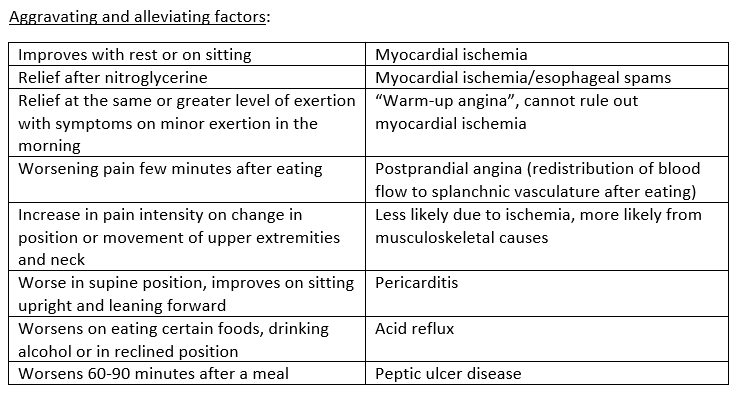

Always ask the following questions: quality of the discomfort, location, pattern, aggravating and alleviating factors, associated symptoms and past medical history.

Angina suggestive of myocardial ischemia usually develops over a few minutes, worsens with activity, and improves with rest. However, if the pain peaks in intensity immediately from onset, consider aortic dissection, PE or spontaneous pneumothorax in your list of differential diagnoses. Chest pain that lasts only for a few seconds is rarely ischemic in origin. Also, chest pain that is constant in intensity for many hours to days in the absence of EKG abnormalities, elevated troponin levels or clinical signs of heart failure or hemodynamic instability is unlikely to be from ischemic causes.

Diaphoresis, fatigue, dyspnea, pre-syncope, syncope, nausea, vomiting and eructation (aka belching) are some of the associated symptoms that you may find in myocardial ischemia.

Dyspnea is suggestive of a cardiopulmonary driven process, and hence, we should also think of PE or spontaneous pneumothorax if there is sudden onset respiratory distress.

Hemoptysis is more common in PE or severe heart failure.

Syncope and pre-syncopal features are more common in hemodynamically significant PE, aortic dissection, or ischemic arrhythmias.

Nausea and/vomiting can be seen due to gastrointestinal causes or in myocardial ischemia (more commonly due to inferior wall MI)

It would be useful to dig deep and find out history that could help incriminate one or more on our list of possible suspects.

Find out risk factors for coronary atherosclerosis including hypertension, hyperlipidemia, obesity, family history of cardiac diseases or sudden cardiac death (SCD) or current smoking status. What always helps is to ask the patient for a list of their most accurate medication list to work it backwards and update their list of medical conditions.

Ask about recent surgeries or instances of immobility, history of current or past hormone therapy or oral contraceptive pill use, or previous episodes of clots in their lungs or legs (venous thromboembolism)

Ask about Marfan syndrome or a family history of the same (aortic dissection), recent upper respiratory infections that resolved over a few days (pleuritis/pericarditis), and depression or mood disorders (panic attack).

Physical Examination

General appearance:

See if the patient appears anxious, uncomfortable, pale, cyanotic or diaphoretic, which could be suggestive of acute MI or another acute cardiopulmonary process.

Vital signs:

Think of the most severe causes of chest discomfort if tachycardia and hypotension exist.

Think of pulmonary causes if tachypnea and hypoxia are prevalent.

Although acute aortic syndrome usually presents with severe hypertension, hypotension may also be seen when coronary arteries are involved or when the dissection involves the pericardium

Low grade fever can be a non-specific finding, seen in MI, PE or in infections.

Pulmonary:

Auscultate the lungs for the following - bilateral crackles, suggestive of pulmonary edema (left ventricular (LV) dysfunction), decreased or absent breath sounds, wheezing or rhonchi.

Cardiac:

Look for jugular venous distension, third or fourth heart sounds, murmurs or pericardial friction rub.

Abdominal:

Localized abdominal tenderness makes it less likely for the chest discomfort to be cardiopulmonary in origin

Musculoskeletal:

Look for localized swelling, redness or tenderness, and joint pain. Reproducible chest pain on palpation cannot rule out myocardial ischemia.

Electrocardiography

Always get an EKG within 10 minutes of presentation for any patient with acute chest discomfort, and serial EKGs every 30-60 minutes to make sure we do not miss out any evolving electrical changes. And yet, resting EKGs only have a sensitivity of 20 %.

Imaging

A plain chest radiograph at baseline is always useful; it is useful to identify pulmonary processes contributing to the discomfort. There are no findings in ACS on a plain film except for pulmonary edema to watch out for. Widening of mediastinum can be appreciated in aortic dissection.

Consider other imaging modalities when there is a high suspicion for an acute life-threatening disease process, for example, CT angiography to look for PE.

Cardiac Biomarkers

If the chest discomfort seems consistent with ACS, we need to measure cardiac biomarker levels. Cardiac troponin is the preferred one, and serial measurements showing rise is suggestive of myocardial ischemia. Just when we were getting used to the world of troponin and chest discomfort, high sensitivity troponin came in to turn our lives upside down. Since this has already been too much of information, let’s touch base on high sensitivity troponins in a later post.

Evaluation and Management

I came across this beautiful flowsheet summarizing what we have discussed (and a lot more).

Figure 2. Algorithm for the initial diagnostic approach to a patient with chest pain. AoD, aortic dissection, c/w, consistent with; CXR, chest x-ray; hx, history; STE, ST elevation; TEE, transesophageal echocardiography; UA, unstable angina; TWI, T wave inversion; V/A, ventilation-perfusion scan. Source: Chapter 35 Approach to the Patient with Chest Pain, Libby P, Bonow RO, Mann DL, Tomaselli GF, Bhatt D, Solomon SD, Braunwald E. Braunwald's Heart Disease-E-Book: A Textbook of Cardiovascular Medicine. Elsevier Health Sciences; 2021 Oct 15.

Figure 3: From Collet JP, Thiele H, Barbato E, et al.; ESC Scientific Document Group. 2020 ESC Guidelines for the management of acute coronary syndromes in patients presenting without persistent ST-segment elevation. Eur Heart J. 2020;Aug 29;ehaa575. https://doi-org.echo.louisville.edu/10.1093/eurheartj/ehaa575

Source: Chapter 35 Approach to the Patient with Chest Pain, Libby P, Bonow RO, Mann DL, Tomaselli GF, Bhatt D, Solomon SD, Braunwald E. Braunwald's Heart Disease-E-Book: A Textbook of Cardiovascular Medicine. Elsevier Health Sciences; 2021 Oct 15.

Using the HEART score and the TIMI risk score along with serial troponin measurements helps risk-stratify these cases and avoid unnecessary cardiac testing by 82 %.

As per ACC/AHA guidelines, for initial management, we can subgroup acute chest discomfort into four major categories: noncardiac, chronic stable angina, possible ACS, and definitive ACS.

Figure 4: Algorithm for the evaluation and management of patients suspected of having ACS.

Adapted from Amsterdam EA, Wenger NK, Brindis RG, et al. 2014 AHA/ACC guideline for the management of patients with non-ST-elevation acute coronary syndromes: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2014 Dec;64[24]:e139–e228.

Source: Chapter 35 Approach to the Patient with Chest Pain, Libby P, Bonow RO, Mann DL, Tomaselli GF, Bhatt D, Solomon SD, Braunwald E. Braunwald's Heart Disease-E-Book: A Textbook of Cardiovascular Medicine. Elsevier Health Sciences; 2021 Oct 15.

To go over management of every cause of acute chest discomfort would make this too long and boring.

Just keep this in mind for the following:

STEMI- Activate the STEMI pathway and let our interventional cardiology team take over the reign. Pat your back, you just diagnosed a STEMI!

NSTEMI/UA- Based on TIMI score, the patient may need an urgent diagnostic coronary angiogram, anticoagulation with antiplatelet therapy and coronary angiogram, and non-invasive stress testing.

Other acute causes of chest discomfort

Acute pulmonary embolism- Start anticoagulation; activate the PE response team if there are signs of right heart strain suggestive of a massive/sub-massive PE

Tension pneumothorax- Needle thoracostomy; consult trauma

Aortic dissection- Based on imaging findings, consult cardiothoracic surgery or manage medically if non-operable

Pranav Pillai, M.D.

University of Louisville | UL · Department of Medicine | Internal Medicine Residency Program

Dr. Pranav Pillai is a second-year member of the University of Louisville Internal Medicine Residency Program.

References:

Chapter 35 Approach to the Patient with Chest Pain, Libby P, Bonow RO, Mann DL, Tomaselli GF, Bhatt D, Solomon SD, Braunwald E. Braunwald's Heart Disease-E-Book: A Textbook of Cardiovascular Medicine. Elsevier Health Sciences; 2021 Oct 15.

National Hospital Ambulatory Medical Care Survey: 2018 Emergency Department Summary Tables. CDC. 2018. Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/nhamcs/web_tables/2018-ed-web-tables-508.pdf

Chapter 11 Chest Discomfort, Jameson J, Fauci AS, Kasper DL, Hauser SL, Longo DL, Loscalzo J. Harrison's Principles of Internal Medicine, 20e; 2018.

Nagam MR, Vinson DR, Levis JT. ECG diagnosis: right ventricular myocardial infarction. The Permanente Journal. 2017;21.

Figure 1: Chapter 11 Chest Discomfort, Jameson J, Fauci AS, Kasper DL, Hauser SL, Longo DL, Loscalzo J. Harrison's Principles of Internal Medicine, 20e; 2018.

Figures 2, 3 and 4: Chapter 35 Approach to the Patient with Chest Pain, Libby P, Bonow RO, Mann DL, Tomaselli GF, Bhatt D, Solomon SD, Braunwald E. Braunwald's Heart Disease-E-Book: A Textbook of Cardiovascular Medicine. Elsevier Health Sciences; 2021 Oct 15.

Image 1: <a href="https://pixabay.com/users/parentingupstream-1194855/?utm_source=link-attribution&utm_medium=referral&utm_campaign=image&utm_content=840125">Parentingupstream</a> from <a href="https://pixabay.com/?utm_source=link-attribution&utm_medium=referral&utm_campaign=image&utm_content=840125">Pixabay</a>

Image 2: https://www.dreamstime.com/stock-illustration-cartoon-doctor-old-man-hospital-image96903260